TIOH Art Tour: Yemenite Megillat Esther Case and Illuminated Scrolls

- Parchment, Olivewood, Silver, Gold, Ivory, Filigree Work, Semi-Precious Stones

- Gifts of the Briskin Family

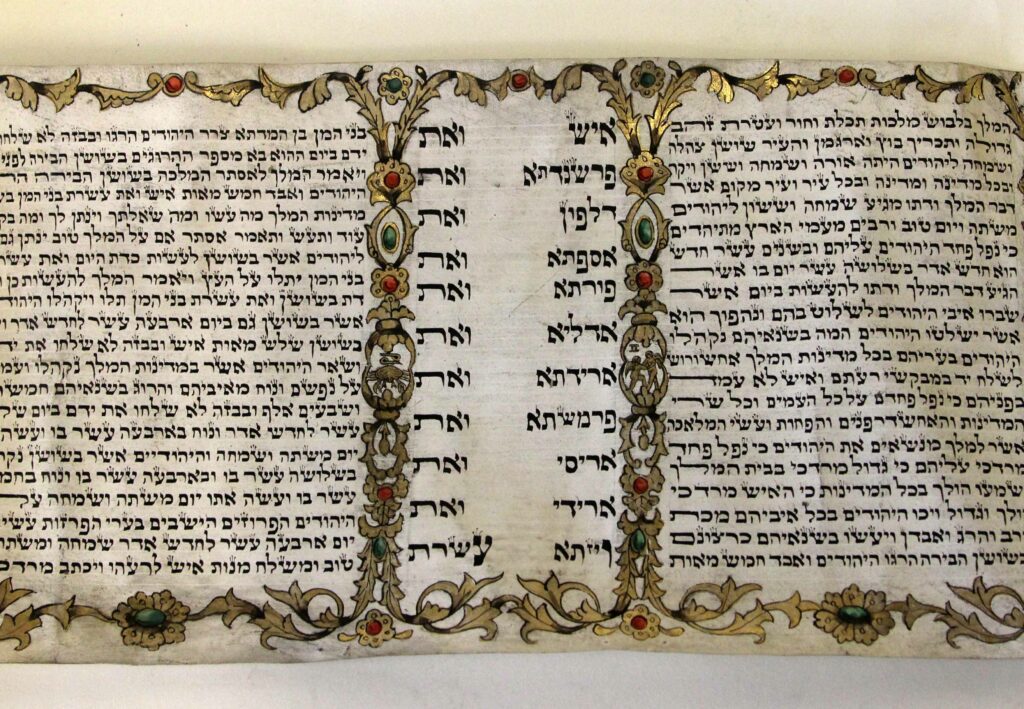

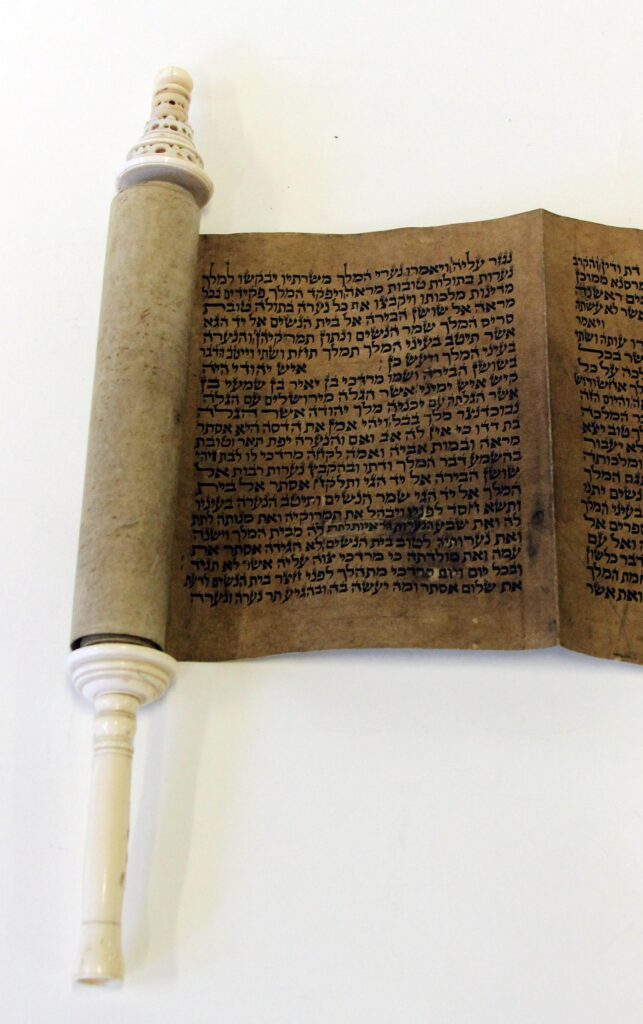

At first glance, this Megillah from late 19th century Yemen is striking in terms of its color, size, and shape: it is severely tarnished, it is nearly 18 ½ inches tall and 4 ¼ inches in diameter. Juxtaposed against its smaller counterpart from 19th century Poland, with its many gemstones, polished silver case, and gilded eagle perched on a golden crown, the Megillah from Yemen seems pale in comparison. Yet, to compare the two in such a manner does not do this Megillah justice.

This ritual object is beautiful in a more profound way. By looking closely at the details, I believe one can see it is a symbol of hope and a testimony to the commitment first made by the Persian Jews at the time of Esther to celebrate Purim in every generation, by every family, in every province, and in every city in remembrance of their escape from the threat of extermination.

Before we examine the Megillah itself, let me provide a little context. Jews had settled in Yemen centuries before the common era, and were valued for their expertise in a wide range of trades that Muslims normally avoided – weapon and tool repair, weaving, pottery, masonry, carpentry, shoe-making, and tailoring to name a few. Interestingly, at the top of the list was silversmithing. In fact, interspersed throughout the rural and mountainous regions of Yemen, there were numerous communities of Jewish silversmiths that established techniques and designs that are still in use today. While thus deeply rooted and valued economically, the Yemenite Jews were in constant fear of discrimination and persecution. Throughout the centuries, their circumstance was greatly influenced by the particular Muslim ruler in power and the degree to which Islamic law was implemented.

Given the tenuous nature of this backdrop, it is easy to understand the appeal of the story of Esther to the Yemenite Jews. Toward the end of the 19th century, in hopes of a brighter future, a mass migration began and a great majority of Yemenite Jews fled to the southern port of Aden (which was under British control at the time) and then on to Palestine.

Now to the Megillah itself. The encasing of the Megillah is silver. It’s brilliance escapes us now due to the extreme nature of the tarnishing, but imagine if it were polished and restored to its original luster. The sheer size combined with the incredible detail of the metal work indicates that this must have been a fairly costly commission. Interestingly, the standard practice of Yemenite silversmiths was to use a percentage and quantity of silver for their work that correlated to the needs and ability of the customer to pay. Silver work was paid for with silver coins. A percentage was then used to create the object and the rest was kept as payment. The silver thaler was the local currency used. It was comprised of 83 percent silver. If a higher percentage of silver was desired, the silversmith would turn to the Saudi riyal, which was roughly 93 percent pure, the equivalent of sterling silver. Surely, quite a few Saudi coins must have gone into the creation of this Megillah.

The style and design of the metalwork, along with the flat top of the casing is distinctly Yemenite. The combination of techniques called filigree and granulation was used to create a simple, yet striking design largely made of circles. Filigree is a form of delicate wire work that began to appear in Yemen in the late 19th century. Granulation is a process that joins small round balls to a base and continues to be a dominant feature in Yemenite metalwork. Embedded in the center of the design around the circumference of the casing are three rows of four circular emblems. These emblems are unusual in that they are representational, a feature rarely seen in Yemenite metalwork, or perhaps more significantly, in the geometric patterning in Islamic art and architecture. The emblems clearly represent the 12 tribes of Israel. Aesthetically, the emblems blend harmoniously with the field of circles in which they sit. Their mere inclusion in the design could suggest either a more deliberate statement of faith in a somewhat hostile environment, or conversely, a feeling of respite in more accepting times.

There are six gemstones on the exterior of the case. The stones are natural rather than precious – amethyst, citrine, smokey and white topaz. While they certainly hint at the tail revolving around royal personages within, they may also suggest an additional story. Notice the heart-shaped amethyst along the top. Was this Megillah perhaps a gift of love? We can’t know for certain, but it was custom in many countries for the bride-to-be to give a Megillah to her future husband as a sign, perhaps, not only of her love in hopes for their future together, but of her commitment to family and to honoring the traditions associated with their shared faith in g-d as well.

The scroll itself is in remarkably good condition. It is made up of thick parchment or velum, most likely from the hide of a sheep or goat. It is a hamelekh Magillah – each column of Hebrew text begins with the work hamelekh, meaning king. The scroll appears to be a replacement made in the early- to mid-20th century. How can we tell this? Its near-perfect condition for one, but also because the Hebrew letters are penned in the block style with a vertical emphasis and without flourishes, a style attributed to slightly more modern and very skilled scribes of European origin. One can only speculate as to the provenance of this Megillah. Nonetheless, one thing is for certain – it has undoubtedly journeyed from family to family, from generation to generation, from Yemen to perhaps Palestine, from Palestine across oceans and continents, and landed hear in Los Angeles to take its special place amongst the many treasures in the collection of Temple Israel of Hollywood. Welcome home!

Home